And No Surprises Please

Written Thought Piece by Adam Goren

This global pandemic reminds us that life can be highly unpredictable. Everyone has their own way of dealing with surprises, but for those of us who are particularly sensitive to social and sensory surroundings, the unexpected can be shocking and overwhelming; the more so when impacted by traumatic events. In this Thought Piece, Adam Goren explores how an aversion to unpredictability for 8 years old Omar who has been diagnosed with autism, sometimes triggers energetic attempts to create a hyper-ordered world. And although this can stifle spontaneity and loving exchange, Adam shows how therapy can help build trust in ‘going with the flow.’

…And No Surprises Please

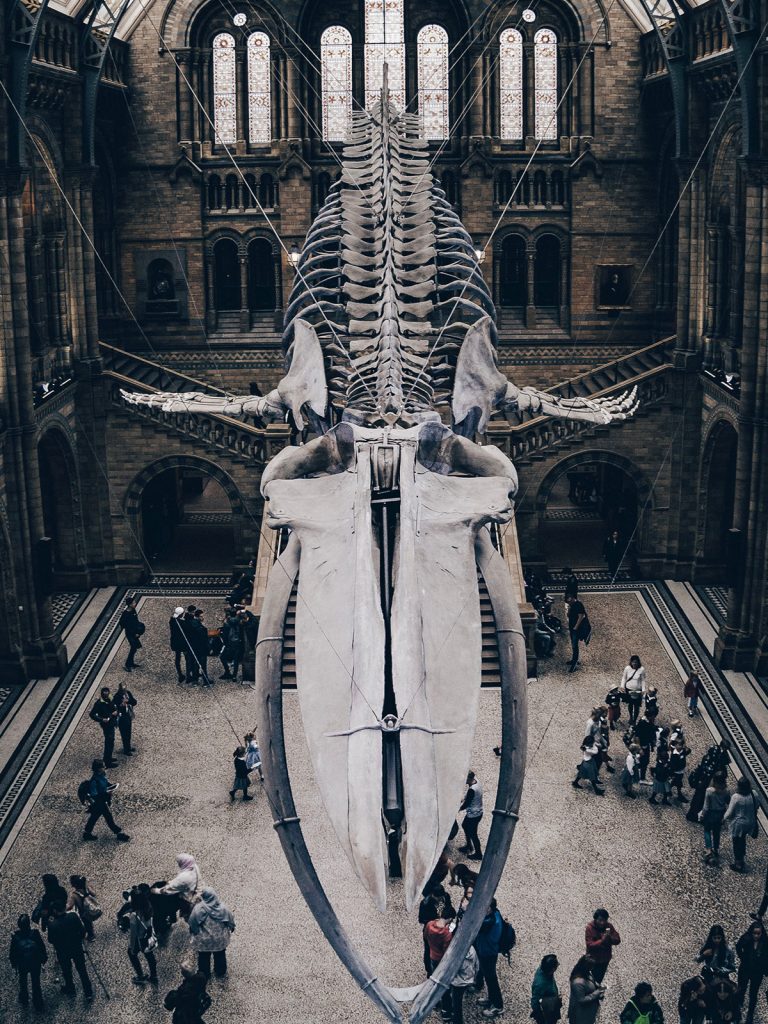

I’d like you to meet Omar. As the Natural History Museum, London, re-opens again, you might find this serious-countenanced 8-year-old in Blue Zone studying mammals. He will be wearing one of two brightly coloured t-shirts: either a green one saying ‘Bettongs Go Beserk’, or a purple one reading ‘Quick As A Quokka’. First though, meet senior curator of Diptera, Erica McAlister. If you’re lucky you will catch her front of house, possibly holding forth on the life cycle of an orange-bearded Bluebottle. In truth, you are more likely to find her in the vast museum archives, making room for yet another newly discovered species of fly, or otherwise abroad hunting flies with her fly-sucking, backpack aspirator.

Photo from Unsplash

Animated, ebullient and not a little mischievous, if you catch Erica talking flies, you’ll find that conversation can slide inexorably towards one of three eye-watering Dipteran details: their dazzling beauty, the size of their genitalia and the shit we’d be in without them. Closing an episode of BBC Radio 4’s science comedy show, The Infinite Monkey Cage, McAlister gleefully leaves listeners with the disgusting vision of an imperilled male fruit fly’s last-ditch act of species continuity, inadvertently ejaculating its spermatozoa into a punter’s pint of nutty ale. What makes this drama of premature termination so evocative? And how do death and sex make such weirdly compelling bedfellows?

The relationship between sex and death was of huge importance to the self-proclaimed progenitor of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud. The nutty-ale-riddle of our determined drive to recreate ourselves in the face of, in spite of and because of impending doom, is something he and his descendants have creatively puzzled over time and again – joining, of course, ranks of similarly perplexed philosophers, scientists, artists and historians through the ages. Freud, or at least one version of this extraordinary man, seems to have been propelled in earnest pursuit of answers to the riddle by a burning preoccupation, not only with the apparently unavoidable conflict of being alive, but with the nature of his own death and legacy.

In a love letter to his fiancée, Martha Bernays, in 1885, the still-youthful relatively-unknown 19th century Sigmund, triumphantly announced the burning of all his papers, (except, of course, those from her and family), declaring that he would confound any biographer’s personal take on his future-famous self. If such a crude analogy tolerates contemplation, Freud, like McAlister’s sperm-laden fruit fly, was heavily invested in securing the future of his chosen progeny. It was as if, against his keener judgement, Freud believed he could leave behind something monumental and immutable, impermeable to more intimate archaeological interpretation. Setting aside the sheer chutzpah of the young man’s ambition, one would like to imagine an ironic older version of the man laughing wryly at this somewhat futile strike against life’s careless unravelling and essential contingency.

Klass Stephan

Fascination with the precariousness of life takes us from a luckless fruit fly, floating in a pint of beer, up through the atmosphere. Here a supranatural pollen-seeded crystal is forming in just the right freezing conditions to create a winged-snowflake, destined to glide around in perpetuity, avoiding the demise of falling and melting. This strange crystalline creature is the creation of acclaimed neuroscientist Karl Friston and his colleague, Klaas Stephan. They use it to illustrate the improbable niche life occupies in the universe and the implausibly organised sentience of it. Friston needs to bestow a kind of Will upon this Snitch-like snowflake, for it to act selectively on its surroundings; that way it maintains its physical integrity in contrast to its background; fly too high or low and it stops being a snowflake. An organism, Friston is telling us in his mind-bogglingly complicated neo-Cartesian theory, exists because it knows it exists; it senses its way through time, continuously intelligently modelling its surroundings, responding to atmospheric changes, and resisting dispersal in seeming ‘defiance’ of the disorder towards which everything is inexorably moving.

Perhaps defiance is the right word for a pre-emptive strike against bedlam, chaos and dissipation. Freud’s and Friston’s projects for scientific psychology seem to share, above all, a privileging of individuation, which Friston, in mathematical statistical terms describes as a Markov blanket. The highest form of this individuation, they both suggest, is the remarkable phenomenon that is our human brain. But when he says, ‘I am in the game of garnering information that maximises evidence for my own existence’, Friston may be letting on more about the kind of game he’s invested in, than just making sense of our brains as inference-making prediction machines. And when Freud tells us, early on in his career, that the human brain is working against the entropic-like pull towards neuronal inertia, he seems to unwittingly shine light on what will be a very public obsessive defence against a very private fear.

If there is one thing that joins Freud and Friston, it is the need to pin things down and make order of the world; not just the everyday domestic order of tucking in one’s Markov blanket or dusting down the relics collection, but a much grander cosmological vision that might help make sense of our senses and of the universe. And so, by association, we might begin to understand how both men could be bothered by the kind of sudden unexpected demise that befell McAlister’s hapless fruit fly.

In her inadvertently self-revealing essay, The Aesthetics of Fear, Joyce Carol Oats needs us to know that what we dread most is not our physical end. What we dread most, she says, is a loss of meaning. ‘To lose meaning’, Oats asserts, ‘is to lose one’s humanity, and this is more terrifying than death’. To lose meaning, she infers, is to lose an internal coherence, to lose one’s senses, to go out of one’s mind; and that, so Friston’s theory suggests, robs us of a crucial sense of what might happen next.

Omar is not a child with a capacity for grand theorising, but this chubby pretty-faced boy, adored by his long-term foster-carer-turned-adoptive-mother, Yasmine, is absolutely consumed with putting things in their rightful order. This starts in the morning with his cereal in the red bowl with the red spoon and not any random one his foster-sister or mum might use. It then pervades every detail of the daily schedule including all significant events, and applies, most of all, to his abiding all consuming passion and safety-sweet-spot, the classification of marsupials.

There are plastic possums and furry wombats all over his home, which doesn’t surprise me, as they’re very cute. But in weekly therapy sessions, Omar admonishes me for my sentimentality. Their cuteness isn’t the point. As this amber-eyed golden-skinned boy gravely pronounces in all pedagogic seriousness – and you need to know here, that his heart-broken Eritrean birth-mother overdosed and died shortly after he was born – ‘about 55 million years ago Metatherians migrated from South America through the Antarctic, where they probably accidentally rafted a short way to Australia, before their route back was cut off forever. Do you know that?’

‘Do you know, Adam?’ was a familiar refrain, which I quickly learnt begged no answer. It was only after many months of work, helping Omar build an easier, less protectively suspicious way with Yasmine, that he trusted me enough to allow himself to find out if I did. He was usually disappointed. Nevertheless, he was also absolutely delighted with my genuine interest, and week by week he let me in a bit. So it was that, in these three-way meets, Yasmine, naturally also a marsupials-expert, Omar and I, evolved a richer deeper exchange of thoughts and feelings. I learnt about the eating habits of bandicoots and he eventually tolerated hearing about, amongst other things, my interest in solitary bees.

Photo from Unsplash

Omar is, unsurprisingly, a fully paid-up member of the Natural History Museum. If there is, for him, one inordinately satisfying feature of this hallowed temple to taxonomy and taxidermy, it is that, unlike all the annoying people milling about, making unnecessary noise and fuss, the specimens are, generally speaking, as predictable as specimens can be, given the occasional irritating exhibition change. And that, of course, is because they’re all dead. For Omar, the museum is like a reassuringly pinned down and predictable version of life’s irrepressible teeming super-abundance. Crucially, there is nothing that might administer a nasty shock.

Most of the children I’ve seen who’ve lost their parents, through one misfortune or another, suffer from a common abiding affliction: an intolerance of uncertainty. Their early lives read like tales of the unexpected: the missile strike of violent parental explosions, the landslide of a sudden move, the inexplicable disappearance, the shocking death. Whilst some children seem to have been born hoping for the best, and then find themselves stunned with incredulity and flinching through mayhem, others, like Omar, seem to have come into the world wary-eyed and readied-up, braced for the worst. All have, one way or another, overdosed on bad surprises.

In the reductionist taxonomy of unease we call diagnoses, Omar would be described as autistic. But it would be wrong to label him as unmoved by people or disinterested in their minds or completely averse to novelty. It is more accurate to say that his intensity of feeling for people, and for life, makes his experience of both feel perilously precipitous. And then storms in teacups easily become teacups in storms, ordinary clumsy comments cut through him as if they are contemptuous acts of betrayal; separations feel terminal. Omar is, one might say, inordinately sensitive to life’s contingency. But whilst fearing imagined imminent ends, he also enthuses with a kind of energy, and loves with a kind of intensity, that can be breathtaking to behold.

Karl Friston

An organism’s function, Karl Friston tells us in his Free Energy theory, is to maximise model evidence of itself and minimise surprise. Omar, Friston might claim, suffers from too big a gap between his fantasy predictions and the sensory reality confronting him; he cannot, that is, match expectation to reality successfully enough to make his experience of the world a more comfortable kind of self-fulfilling prophecy. Encouraging him to see and feel things slightly differently is his mum’s way of helping him close the gap, although, from my point of view, her loving commitment is perhaps as much convincing as he needs.

At the same time, autism, in its varied forms, is too easily classified as a disorder of perception. Some of those in our midst diagnosed as being ‘on the spectrum’, like the activist Greta Thunberg and the naturalist Chris Packham, show a singular gift for feeling and expressing the fullness of life on earth, red in tooth and claw. These remarkable individuals are too easily characterised as over-alarmed faulty predictors. They are, perhaps, more like Geiger counters of our potential radioactivity; signalling the challenge we all face in sustaining our continuity, and reminding us how difficult it is to live and love together whilst in a state of personal and collective apprehension. They are also, let’s not forget, surprisingly good at surprising us in good ways; training sharp-focussed lenses on the inexplicable fecundity, frighteningly riotous aliveness, and uncanny agency of what is in us, on us and all around.

Dedicated in memory of Gabi Shaked, who died very young.

This case study is inspired by real cases and is not a factual account.

View more in-depth thinking from our guest bloggers on our Thought Pieces page.